Grant's Gear Pages

Page 1: Keyboards & Synths

The Paper-Round Years (1979-1988)

Electronic Dream Plant (EDP) Wasp

The Wasp was my first real synthesizer. I had put down a deposit for a brand-new one in Thomson's Music in Glasgow.

If memory serves, it cost £225 - around about £700 in today's money. Luckily, I spotted an advert for a second-hand

one in the classified ads of the Glasgow Evening Times. I got the Wasp and a 30W guitar combo amp for £120. And thus

started my lifelong medical condition known as G.A.S. (Gear Acquisition Syndrome).

The Wasp was a very dirty, overdriven, electronic-sounding thing. In fact, I was about to describe it as the kind

of synth you would expect Throbbing Gristle to create. Imagine my surprise to find that Chris Carter had written

a retrospective review of the Wasp for Sound

on Sound magazine.

Casio VL-Tone

I first became aware of the VL-Tone when I saw it on Tomorrow's World. I'm pretty sure it was Kieran Prendiville demonstrating

it, programming in "There'll Always Be An England" for St George's Day. They didn't mention a price, but when I saw the

combination of synth, sequencer and crazy beat-box, I thought it would be the best part of £200. When I found out that it

was only £35, it was a complete no-brainer.

The ADSR function was pretty cool, and I can still remember some of my fave 'patches':

70099924 for octave-hopping bass (particularly nice when used with Rhumba rhythm).

50099930 for quite a meaty bass.

The internal sequencer allowed entry of up to 100 notes, and you could 'tap in' the timings later, which was a nice feature.

The first movement of "Monolight" by Tangerine Dream uses a sequence of six chords - C, Em, Am, F, Dm, G. Playing two bars

of arpeggios for each chord gives a grand total of 96 notes. The 'Repeat' function allows you to replay your sequence four

times before auto-stopping. So, armed with a VL-Tone and my trusty Wasp, I could play a half-decent cover version of one of

my all-time fave tunes!

Casio MT-30 / MT-40

The MT-30 was one of the first Casio 'multi-instrument' home keyboards. It was my first polyphonic keyboard. Most of the

22 available sounds were at the very least 'useable', with a handful of them being really first-class. My all-time fave

was preset 16 - Trumpet. If you put it through chorus or delay, you could just about convince yourself you were listening

to a Juno 6.

Later on, I traded in my MT-30 for an MT-40. This featured exactly the same set of sounds, with the addition of a simple

pre-set rhythm, bass and auto-accompaniment unit. It seems amazing that we used to go out gigging with such machines, but

there you go.

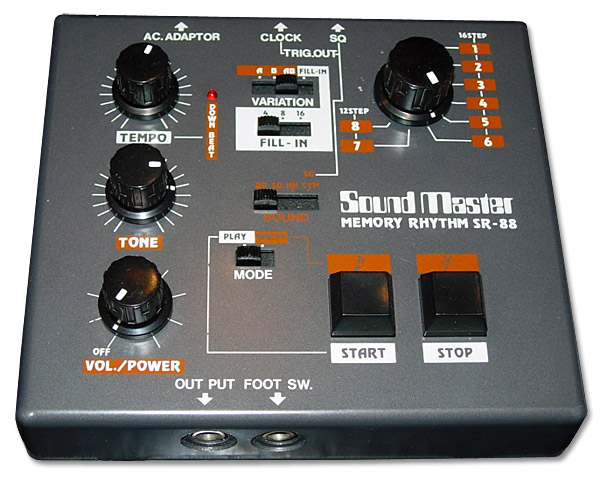

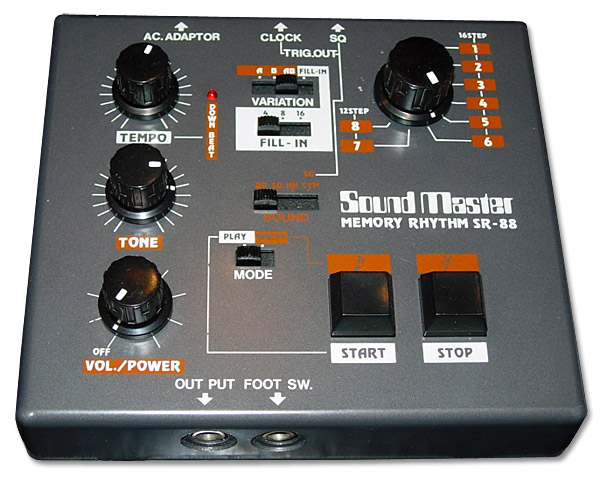

SoundMaster SR-88 Drum Machine

The eagle-eyes amongst you will have noticed that the SR-88 is neither a synth nor a keyboard. It's the only drum machine

I've ever owned, though, so a separate page for beat boxes would seem a bit daft. Consider this page a 'sound generator' page

and we're all good.

The SR-88 came with four sounds - Bass / Kick Drum, Snare, Closed Hi-Hat and Open Hi-Hat. These could all be programmed

independently on a 16 or 12 step grid pattern. The open hi-hat could also be used to send a gate pulse to an attached

synth - a feature I used heavily with both the Wasp and SH-101. There was also a 16-beats-to-the-bar clock output which

could drive an external sequencer or arpeggiator. Each pattern had an alternate pattern which could be used as an extra

storage location, or which could be switched to automatically every 2, 4, 8 or 16 bars as a 'fill-in' pattern.

Programming was fairly straightforward by entering beats or rests for each step in the bar on each instrument in turn. It

sounds a bit complex when written down, but becomes second-nature when doing it for real.

Roland SH-101

The Roland SH-101 was a replacement for my Wasp. In those days, I couldn't afford to keep a huge collection of synths,

so every new purchase pretty much meant having to sell an older piece of gear to finance it.

The SH-101 was a cracking all-rounder and became the backbone of our little electro-pop band. It was dead reliable and

the tuning was rock-solid from the second you switched it on.

Overall, it was a very well thought-out machine. The only niggles I had were:

1. Having to hold down the Transpose button and press a key simultaneously to transpose a sequence. The keyboard was

inoperative when the sequencer was running, so I don't know why they didn't make transpose the default mode (like the

Pro-One).

2. The square-wave modulation on the VCO was bipolar, meaning that it trilled 'around' a frequency. Had it been unipolar,

you could have created pseudo-arpeggio effects, alternating between root note and octave or fifth.

3. The white noise was a bit 'crunchy' sounding, but it was good for percussion and thunder!

Casio CZ-101

The Casio CZ-101 was my first proper programmable polysynth. Casio really pulled off something incredible

with the CZ-101. It was digital, but the sound-generation engine was reassuringly analogue-like in terms

of sounds. Also, the programming paradigm was reassuringly subtractive-like, in stark contrast to the FM

craze that was sweeping the synth world at the time; within minutes of unboxing mine, I was tweaking

parameters right, left and centre, with a reasonable chance that I would achieve my intended goal.

It came along later than the DX-7, and was in many ways an 'inferior' machine. But I would much rather

have a genuine CZ-101 in my collection today than a genuine DX-7. I think the programming experience was

the main deal-breaker for me. I was always much more interested in using synths to create new electronic

sounds, and imitative synthesis of other instruments was way down my list of priorities. I know that most

keyboardists of the time took a polar opposite view of things, and that's fair enough - DX-7 sales figures

show that Yamaha made all the right decisions at that point in history.

Anyhow, the CZ-101 provided a very comfortable approximation of analogue sounds with its Phase Distortion

sound engine. The sweeps from sine wave through to sawtooth wave or square wave sounded more natural than

the FM sweeps offered by a DX7. So most of the techniques that people had learnt through years of using

analogue monosynths could be applied with minimal change. Yes, it was a limited palette, but having those

limits meant that you wouldn't waste time chasing the chimera of what you think 'should' be possible. I keep

coming back to the DX-7, but Yamaha stated outright that a 6-operator FM algorithm could generate ANY fixed

spectrum waveform you desired. What they were careful NOT to claim was that you could get any DYNAMIC

wave transformation, such as that offered by the ubiquitous Low-Pass Filter. People who spent literally hours

trying to coax a low-pass filter sweep from a DX-7 would end up empty-handed (and achey-headed).

For its time, it also had a few surprises in store. The most impressive feature was that you could make it

four-channel multi-timbral over MIDI. Computer-based multi-channel sequencers were slowly emerging, and it

was possible to set up the CZ-101 to be a poor-man's Vince Clarke, with bass, lead, chord and percussion

backing. It came with guitar strap studs out-of-the-box, and the pitch-bend wheel was in just the right

position when using it in sling-on mode. You could layer patches, which admittedly took it from the regular

8 voice polyphony down to 4 voices, but again, this trumped trying to create a layered patch on the DX-7

by using algorithms with parallel stacks of operators.

Sheesh - I didn't think I'd end up writing so much about the CZ-101. Another cracking release from Casio,

providing great functionality for synth users at the budget end of the market!

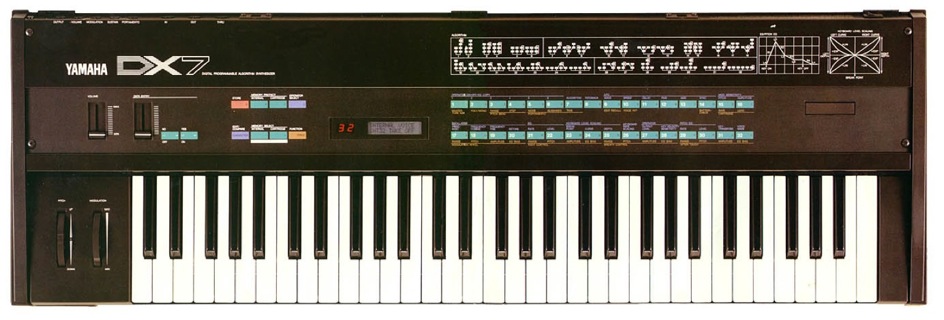

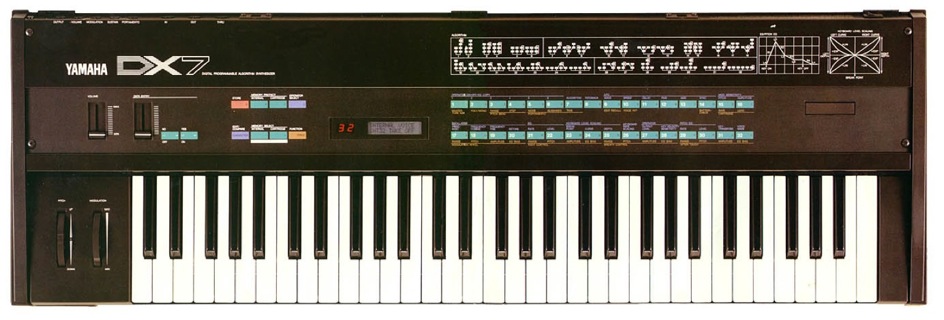

Yamaha DX-7

Just to prove that my gushing review of the CZ-101 was not sour grapes, I did in fact own a TX-7 rack and

used it a fair amount in my early tape recordings, and I had a fair bit of experience using the full

keyboard version through various friends at the time.

I first became aware of the DX-7 (actually, looking at the front panel, I'd better start calling it the

"DX7") in the July 1983 edition of Electronics

and Music Maker Magazine. (The one with Mark Kelly of Marillion on the cover). There was a multi-page

interview with Dave Bristow about the DX7, DX9 and FM synthesis. Re-reading that article with the benefit

of hindsight (well over 30 years later !), I can't help shaking my head at the attempts to sow the seeds

of "The FM Mythos". The wisdom of the time said that FM synthesis (and, by extension, Yamaha's DX range

of keyboards) would actually REPLACE subtractive synthesis (and, by extension, all keyboards from all other

manufacturers).

I have to admit, that for a gigging pub covers band, the DX7 ticked all the boxes:

- 16 voice polyphony at all times

- rock-solid tuning stability

- sturdy construction, which could withstand a lot of abuse on the road

- velocity-sensitive, semi-weighted keyboard with aftertouch

- pitch and mod wheels, with a heap of expression inputs as standard on the rear panel

- instant recall of patches from internal memory or plug-in cartridges

- a good collection of very useable factory-programmed presets

History showed that Yamaha played a blinder at that point in time. Delivering all these features at that price point

was quite an achievement, no matter which way you slice it. It was truly a no-brainer for a

pro or semi-pro keyboard player to have a DX7 as the main machine in their rack, or indeed to have it as their sole

instrument.

However, most of these features didn't really intrigue me anything like the promises of FM synthesis itself.

First off, it was DIGITAL. To the best of my knowledge, reading a magazine article in those dark pre-internet

days, the DX7 would be able to generate ethereal pads, Synclavier & PPG-like metallic clangs, breathy choirs,

etc, etc, etc. I first heard one "in the flesh" at Thomson's Music on a Saturday afternoon. The sales assistant

was demonstrating internal presets 1 to 32 in turn. When he selected sound 26 - Tubular Bells, I LITERALLY went

weak at the knees; I simply couldn't believe that such a pure, present sound could be created on a synthesizer.

It was literally like there were metal doorbell chimes under each key, not some computed waveform coming out of

an amplifier speaker.

Moog Rogue

I joined a rock / prog covers band when I was at Strathclyde Uni, and became more interested in synths as

keyboard instruments to be played in real-time. The SH-101 was my main lead monosynth at that time, but when I tried out

the Rogue in Sound Control (Saltmarket), I knew that I had to make the swap. (I'm sure the sales staff were amused

that I still pronounced the manufacturer as M-"oo"-g, even though the synth acted as pronounciation guide for Dr Bob's

surname). It just had THAT Moog lead sound, with two slightly detuned overdriven sawtooth waves going through a patent

Moog Ladder Filter.

The front-panel controls were very stripped-down, but I think Moog made all the right decisions in balancing

out switched vs fully variable parameters. You could coax a surprisingly wide range of very useable sounds out

of the limited number of parameters, sometimes even quite delicate and sweet patches. The single envelope

generator is a simple AR design, with sustain level switchable between 0 and 100%. The VCA can be switched

between keyboard gate signal, bypass (on all the time) or the envelope generator. But again, the number of USEFUL

variations that this basic setup provided was very flexible for something which would be used predominantly as a

live lead or bass synth. Interestingly, the envelope amount could be used to sweep the frequency of Osc 2 when in

Contoured Sync mode. This gives you that classic Sequential T8 swept sync sound. Sweep magnitude is controlled

by the "AMT" slider on the filter's panel.

Talking of the filter, yes it's the classic Moog Patent 24dB / oct transistor ladder filter. It can of course

be made to self-oscillate, which allows you to make lots of sci-fi sounds when you modulate the cut-off frequency

using the envelope generator and modulation oscillator. Surprisingly, the keyboard tracking amount is provided

by one of the few rotary knobs on the front panel (which is mostly populated by switches and sliders). Mark Doty

is as perplexed as me as to why Moog chose this function,

rather than Cut-Off Freq, to be given the privilege of having a dedicated knob.

The LFO can be routed to modulate oscillator frequency and/or fliter cut-off, with modulation depth being controlled

by the classic Moog mod wheel. Unfortunately, one of the shortcomings of the Rogue's architecture is that you can't

modulate the freqency of Osc 2 independently of Osc 1 when the oscillators are in sync mode. This was a favourite trick

of mine on the Pro-One, which gave you a lovely shimmery sound. I don't know if this would have required quite a few

extra components to achieve this one effect. Like I say, the Moog engineers did a great job in choosing which

features to bring out to the front panel, so that you can switch to new and useable sounds pretty much in an instant.

The LFO provides bipolar triangle wave, unipolar (yay!) square wave and sample-and-hold/random. A nice addition is

the "Auto-Trig" switch which triggers the envelope generator at the LFO rate, useful for pseudo-arpeggios and

sequencer effects.

An unusual, and very welcome, feature is that you can add external signals into the filter mixer. This overrides the

white noise generator on the mixer panel. I was able to get some pretty meaty overdriven Hammond sounds by feeding

my CZ-101 through the Rogue and cranking up the volume.

Overall, a very cool wee machine that I would be happy to have in my keyboard rig again. I have two main gripes with

it, though:

1. The power supply is decidedly non-standard, and Sound Control had to get their engineer to make up a replacement

for me, as the model I bought (second-hand) didn't have the original Moog supply.

2. The oscillators were typically Moog, and took aaaages to get in tune after switching on.

Casiotone CT-202

The Casiotone CT-202 was an addition to my prog band keyboard rack, so that I actually had two polyphonic

keyboards available to me - this and the CZ-101. The CT-202 was an example of the many "multi-instrument

keyboards" that Casio released in the early '80s. You could select from 49 preset sounds by sliding the

'Play/Set' switch to the 'Set' position, and choosing the preset by pressing the appropriate key on the

full-size, four-octave C-C keyboard.

Like the MT-30, MT-40, and the rest of the Casio multi-instrument keyboards, the sounds were created using

a synthesis system known as "Vowel - Consonant".

Essentially, this consisted of two waveforms which had

their own unique amplitude envelopes and fixed-frequency analogue low-pass filters. This allowed for a limited

amount of timbral motion in the sounds, as you could fade harmonics in and out over the duration of a note

- a very rudimentary kind of vector synthesis. Indeed, one particular Casio - the MT-65, allowed the user to select

different envelope variations independently on each waveform. This could lead to weird 'digital' sounds which you

might expect to have come out of a more expensive machine, such as a PPG Wave.

Like most of the Casiotone range, the quality of the presets varied considerably, but I personally feel that

Casio did a better-than-usual job of providing a selection of very useable sounds, and a handful that were truly

excellent. The Harpsichords, Pipe Organs and Bandonion were my favourites. I suspect that Casio viewed the

CT-202 as a semi-professional keyboard, with its full-sized keys, sturdy case, mains power cord and provision

for sustain and volume pedals to be plugged in at the rear. Indeed, Steve Reich was quoted as being happier

touring with a few CT-202s than using DX7s in the mid-'80s! And Viv Savage was confident enough to use one

(and an MT-30!) during a gruelling North American tour.

Casio SK-5 Sampling Keyboard

The Casio SK-5 sampler was a bit of an impulse buy. I knew it was pretty much a toy, but I thought it could

be interesting to have a play about with sampling, even if it was decidedly lo-fi. The sampling capabilities

were actually quite well chosen. You could have any combination of four short samples (in locations 1, 2, 3 or 4),

or two long samples (locations 1 & 2, or 3 & 4). In addition to being able to select any sample to be played

melodically on the mini-keyboard, you could also trigger the samples multi-timbrally through the right-hand

set of four 'drum pads'. The left-hand drum pads would play fixed samples of "Lion" (!!?), "Lazer Gun" (!!?)

and low & high bongos. Talking of drums, there were 10 built-in rhythms, and it was possible to record anything

you played on the keyboard into memory by using its one-track real-time sequencer. I think it was

possible to record (4-note) polyphonic parts, and it may even have remembered whatever you played on the

sample pads, too.

You could apply rudimentary effects to your own samples, such as looping and reverse, and you could apply

different envelope shapes, including a couple with fake 'reverb' tails. As well as custom samples, there

were ROM presets including a remarkably good piano and PPG-ish vocal 'chorus', besides the less useful

sounds such as the of-its-time 'barking dog'.

Sampling quality was not great. There was an internal mic, or you could connect an external mic or

line-level input. I found that you could get the best results by using the line input and an old 'home

computer' mono cassette recorder's 'ear' output. I don't know what the technical spec was, but the anti-aliasing

and reconstruction filters were pretty severe, leading to very muffled sounds. This prompted me to instigate

some 'circuit-bending' (before such pursuits had a name). I managed to identify the pin on the custom VLSI chip

which had the unfiltered DAC output. I connected this to the external mic socket and cut the circuit board tracks

which led back to the sampling preamp. This gave you a bright signal which had loads of digital artifacts at

the top end. This could work quite well for sounds like snare and cymbals. In fact, Roger Linn used a similar

trick to make the noisy sounds on the Linn Drum brighter. By using that bright, unfiltered sound, then feeding

it into a synth's 24dB/oct low-pass filter, you could get lots of interesting effects. Tweaking the filter

cut-off and resonance settings helped to bring out the best in the sound in use at the time.

I remember doing some very lo-fi acid house mixes by sampling bars of music into the 'long sample' slots. By

timing it right, you could perform looping by hitting the drum pads alternating from one bar to the next. For

example, if you sampled into the long slot made up of memories 1 & 2, you could alternate hitting and holding

sample pads 1 and 2 to keep the beat rolling along. Similarly, you could have another bar in long slot 3 & 4,

and keeping it going by alternating between sample pads 3 & 4. By carefully timing things, you can introduce

variations or fills by hitting and holding the four pads at the appropriate times.

I only ever used it on one Under the Dome recording, and that was during the track 'Hell'. There's a sampled

biscuit-tin 'phased gong' during the early 'mayhem' section. It sounds like this sound might not have made it

into the final mix, but it can be clearly heard on the multi-track masters. The second example of its use is

during the first main sequencer section. I sampled various 'guitar licks' from the ESQ-1 into the four sample

slots and triggered them by tapping the sample pads at the appropriate times (10:55 on the CD version). The

timing was thus a bit snappier than I'd have been able to play directly on the ESQ-1 keyboard. If memory serves,

I recorded clean phrases from the ESQ-1, then used the REX-50 distortion on playback so that extra top-end

would be artificially generated, side-stepping the limited sampling bandwidth to a certain extent.

To be continued...

E-Mail Grant