Grant's Gear Pages

Page 3: Software and DAWs

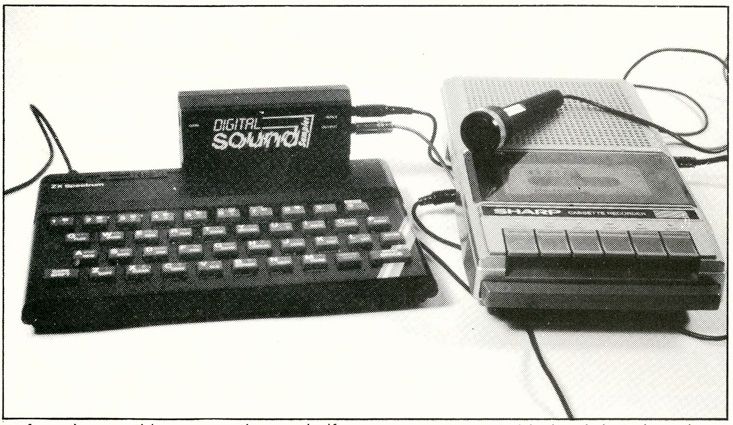

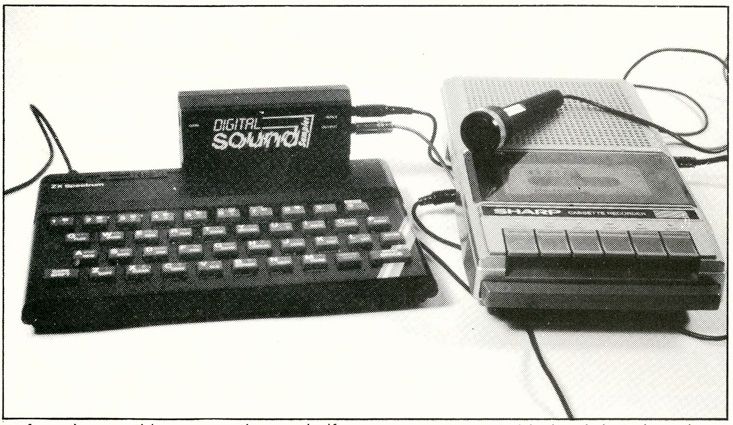

Datel Digital Sound Sampler for Sinclair Spectrum 48K

I bought the Datel Sound Sampler for the Spectrum via mail-order, after reading a

review in the April 1985

issue of Electronics & Music Maker magazine. This was at a time when sampling was still a mystical

technology available only on high-end instruments like the Fairlight and Synclavier. After

plugging it into the back of my Spectrum and loading the software from cassette, I was able

to record and play back all sorts of sounds in glorious 8-bit resolution. The supplied software

consisted of various utilities such as echo (with a hardware feedback level preset pot,

accessible with a small screwdriver). There was also a musical keyboard which allowed you

to play back samples at different pitches.

Things really got interesting when I got down to writing my own software to drive the hardware,

though. Basically, the hardware consisted of an Analogue to Digital Converter (ADC) and a Digital

to Analogue Converter (DAC), with the necessary circuitry to provide an anti-aliasing filter on

the input and a reconstruction filter on the output, as well as input gain and feedback.

Recording audio consisted of reading the ADC in a tight loop and storing the values in RAM.

Playback consisted of reading the values in RAM and sending them to the DAC in a tight loop.

Different playback pitches could be achieved by altering the time between outputting values

to the DAC, or by taking different step sizes when reading through the sample data in RAM.

My first project was to create a pitch shifter. I read values from the ADC into a table in RAM.

If memory serves (no pun intended), I made the table 256 bytes in length so that I could perform

"fixed point" maths using two 8-bit registers as an integer:fraction pair. If you set the

replay increment value to 256, this would step through the sample values at exactly the same

rate as which they were being written. Setting the increment value to 512 would mean that you

would replay the sample values at twice the rate at which they were being written; this would

create an upwards pitch shift of one octave. Of course, this would mean that you would quickly

run out of values to read. The table could be considered a circular loop of tape, with the

record head running round at a fixed rate, and the replay head running faster (for an upward

shift) or slower (for a downward shift). Eventually, the two heads will pass each other, which

could lead to a discontinuity in the output waveform, causing a click or glitch, depending

on the input waveform. Anyhow, the system worked remarkably well, allowing you to create

real-time chipmunk and demon voices. Applying a bit of hardware feedback led to upward or

downward spirals of sound. Admittedly, due to the 8-bit resolution, noise would eventually

swamp any desired sound.

My next project was more involved. It was a Phase Distortion Wavetable Synthesizer. Like

the pitch shifter, I built up a series of wavetables, each one 256 bytes in length, so that

I could use the same integer:fraction increment value for choosing the playback pitches of

two 'virtual oscillators'. The contents of each wavetable were calculated offline to allow

the creation of dynamic timbre and amplitude envelopes. Like the Casio CZ-101, there were

a limited selection of phase distortion wave pairs (carrier and modulator). Off the top of

my head, there were two or three FM sine pairs, sine to square and sine to sawtooth

transforms, some hard sync sounds and some 'phase offset' waves which allowed you to perform

vibrato by quickly varying the starting phase of each oscillator. A musical keyboard was

laid out on the 40-key QWERTY Spectrum keyboard. I was so pleased with the program that

I sent it off on a tape to Datel with a view to them supplying it with the sampler. I

heard nothing back. :(

Next up was a multi-timbral drum machine. I wrote this with a view to actually using it

for recording or jamming, and not just as an intellectual exercise. I calculated that

it would be possible to add the output of three virtual playback channels together

within the time allowed for one sample replay period. I created an editor which was

a little bit like the Fairlight Page R sequencer, with a grid of 16 beats on the X

axis, and three channels on the Y axis. Each grid location could contain a sample

number (1 to 8) or a rest. To create accents, you could place the same sample number

on two or three of the channels at the same beat location. The editor allowed you to

build up several "bars" in memory and then chain them together into a "song". It was

surprisingly useful as a drum machine, and could even be used as a poor man's

Fairlight if you chose suitable samples as your source. In many ways, it was quite

similar to the hugely successful

Cheetah Specdrum,

with the important

distinction that you could sample your own drum kits (or any sample set, for that

matter).

d-lusion RubberDuck TB-303 simulator

I downloaded a shareware demo of this when I was at DMA in 1996. A few of us clubbed

together to buy a license for the full version. I think it was the first genuine

virtual analogue softsynth I'd heard which really lived up to the promise. You can

download it for free

these days from the

d-lusion website (along with

many other interesting applications).

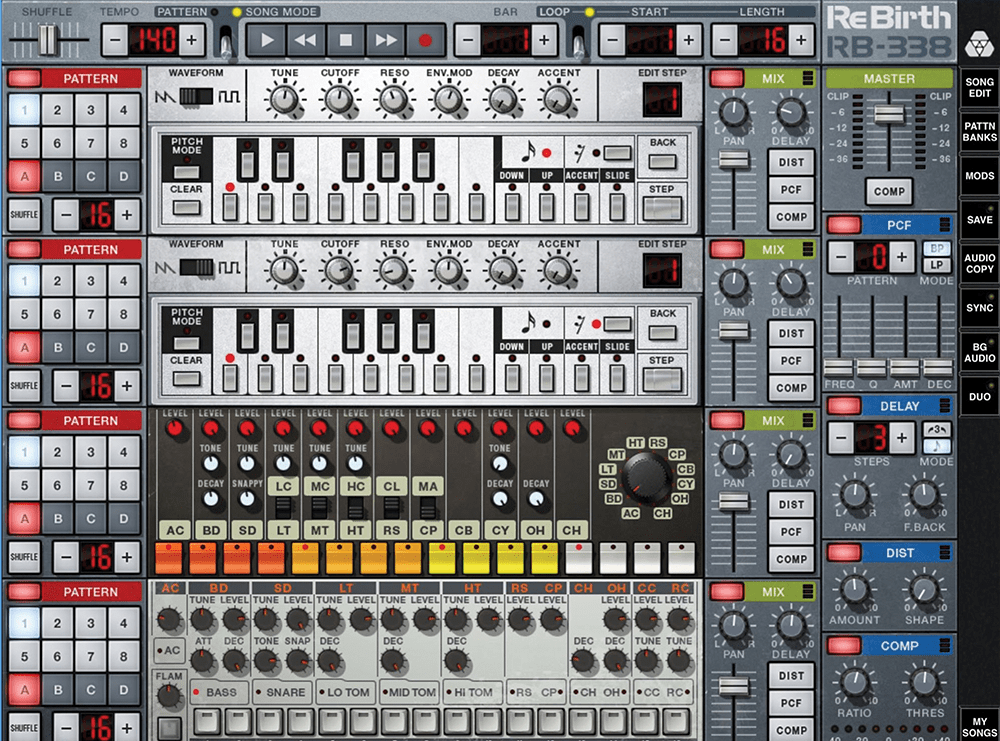

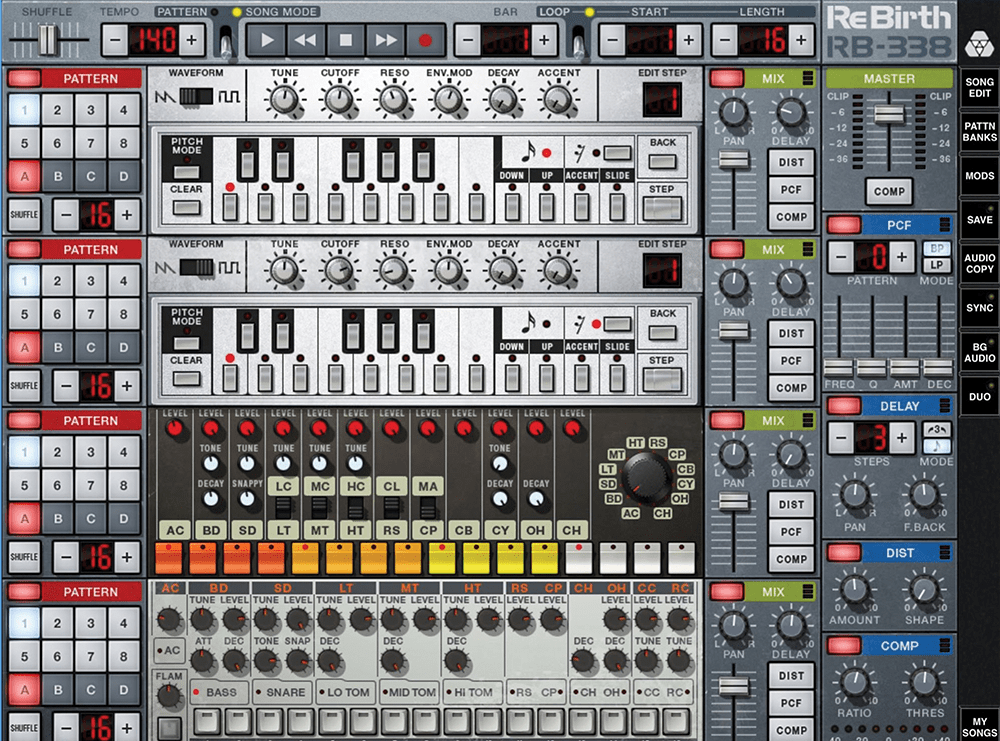

Propellerheads Rebirth RB-338 TB-303 / TR-808 simulator

I was gobsmacked by Rebirth when it was released in 1996. I guess that both the

original TB-303 and TR-808 were starting to achieve iconic (and overpriced) status

by that point in time. To hear them replicated so closely in software, and to be able

to run it on mid-'90s PC hardware, was an outstanding achievement. Propellerheads

(now Reason Studios) went on

to develop the very first version of Reason in 2000,

and it was similarly able to run efficiently on fairly modest equipment.

n-Track Studio

Since using the Pro-Tools III setup at DMA Design, I had always dreamed of being able

to run it (or something similar) at home. That "something similar" appeared in the form

of n-Track Studio for Windows. It was available to download in a demo form, with

restrictions on the number of tracks you could use, and what effect plug-ins you

could apply. It was a good marketing strategy, as it let me test out its usefulness

for my purposes. After a few days use, Colin bought a full license for it, and it

became the Under the Dome studio software for a few years. In fact, Bellerophon

was mixed in n-Track Studio, and the track 'Return' was completely 'moused' into the

piano-roll MIDI editor, without a single note being played on a musical keyboard.

n-Track Studio had most of the features of Pro-Tools, such as mixdown automation,

DSP plug-ins for effects and softsynths, and a non-linear recording paradigm. My

single gripe with it was that it would often lock up completely when you were setting

automation points on audio tracks. I had to get into the habit of saving tracks

before attempting automation editing. Apart from that, it was a fantastic system,

which supported Direct-X and VST plug-ins, and VSTi synths. I even upgraded to the

24-bit version when I bought the M-Box, preferring it to the Pro-Tools LE software

which came bundled with the hardware.

Pro-Tools LE

After Colin left DMA, he bought himself a full PT-III system second-hand and it

still resides at Dome Studios North (though sadly dormant for many years). When I bought

my M-Box audio interface in 2005, it came bundled with Pro-Tools LE, which worked

completely in software. The demo song that came with it really showed off how powerful

a system it could be. The more powerful your processor and the more memory and disk

space you had available, would allow it to expand the number of tracks available and

the number of effects plug-ins you could run. Sadly, I never really had the time to

fully explore recording music on this system. I was bitterly disappointed that I

couldn't use the M-Box on Windows after the introduction of Vista / Windows 7. I

ended up giving it to my nephew Craig, along with a second-hand Windows XP machine.

Propellerheads Reason Adapted

As well as Pro-Tools LE, the M-Box came bundled with "Adapted" versions of Ableton

Live and Propellerhead Reason. I must admit that I never really formed much of a

relationship with Ableton, but Reason was right up my street. If memory serves,

you had a fixed rack with two instances of SubTractor, one of the NN-19 sampler

and one of Redrum. It was limited in many ways; for example, a patch that you

constructed for NN-19 was tied to the song you created, and could not be stored

off as a separate disk file. As you can imagine, building up a multi-sample patch

such as Mellotron Choir was a lot of work to have to replicate every time you

created a new song. However, once again, it was a great marketing ploy on the

part of Propellerheads (now simply Reason Studios), to give out a restricted

copy of the full suite free of charge. From that point on, I was very interested

in getting a full copy of Reason, especially after hearing what Colin could achieve

with it for the UtD track "Philadelphia Experiment".

Propellerheads Reason 4.0

Back in the day when Reason was still a self-contained real-time MIDI-driven

software studio, it was possible to download, ahem, "Evaluation Copies" (AKA

cracked software) from your friendly local neighbourhood torrent tracker. I

found a version of Reason 4.0 with a bundled key generator and so had access

to the full version of it (complete with Orkester sample disk). I have to say

that I was blown away by the quality of many of the instruments and effects

available, and just how efficient it all was in terms of CPU load. I never

actually used the recording and mixing side of things to any great extent,

and ended up using it mostly as a real-time softsynth played from a remote

MIDI keyboard (Alesis QX49, which I still use to this day).

I created many

multi-sampled soundsets for NN-19, particularly Mellotron tapesets from Klaus

Hoffmann-Hooke's archive CDs. I've never been a fan of sampling as a

synthesis method, with two notable exceptions: sampling individual percussion

sounds for a drum machine, and multi-sampling over the entire range of an

instrument. As a result, I really had to wait years for

it to become possible for a home recording hobbyist to be able to throw huge

amounts of memory at a multi-sampled sound.

The other module I found to be incredible was the

Thor Polysonic Synthesizer. You can create patches using pretty much every

synthesis technique available from the analogue sounds of the '70s, through

to PPG wavetable techniques, FM synthesis, Phase Distortion, etc. To this day,

Thor is my go-to synth for pretty much anything, except those few occasions

where I require very special machine-specific quirks, such as the MiniMoog

filter or its envelope response. The main drawbacks with Reason were the lack

of audio tracks and the inability to add third-party VSTs to the rack.

These two factors could be mitigated to a certain extent by running nTrack Studio

in sync through Re:Wire, but it was such a complete faff that it drained

you of any creative impulses before you even got started.

Arturia V-Collection Classics

Of all the genuine vintage synths I had always dreamed of owning, the MiniMoog

would have to come in at Number 1. There's something so electric about its sound,

and it has been responsible for so many of the synth sounds that blew me away

when I was growing up. Sadly, the chances of me actually being able to own a

genuine one seemed very remote, even during the late '80s, when I got into synth

collecting in a big way.

The Steinberg Model-E softsynth showed that it was

possible to create MiniMoog-ish sounds purely in software, and that there was

nothing inherently 'magical' about the analogue hardware. However, as soon as I

had a play about with the Arturia Mini V demo, I knew that someone had got about

close to the real thing as possible - or at least something which did everything

that I would require of the real thing! Of paramount importance to me was that:

1) The oscillators would continue in the background, even when the output was silent.

2) The envelope generators wouldn't reset to zero when a new note was played.

In fact, the Mini V envelopes even do that weird 'increasing attack peak' trick as

heard when rapidly retriggering notes on the real thing - an effect most beloved

of Gordon Reid at Sound On Sound.

As well as the MiniMoog, the V-Collection Classics package contains the ARP-2600,

Prophet 5 / Prophet VS, Jupiter 8, Oberheim SEM and Analog Lab. Of these, only the

ARP 2600 gets any real play time from me. I love it squelchy filter, so reminiscent

of Steve Hillage / Miquette Giraudy. It's great for creating 'modular' FX patches,

too. Mellow brassy lead sounds also seem to be a particular forte of the ARP. Although

the Jupiter, Prophet and SEM are all good in their own way (and remarkably good

emulations of their namesakes), I guess I'm just not a huge fan of analogue

polysynths. Somehow, I'm much more drawn towards digital polysynths, and even more

weirdly towards 'paraphonic' half-way-house analogues such as string synths. Which

brings me neatly to...

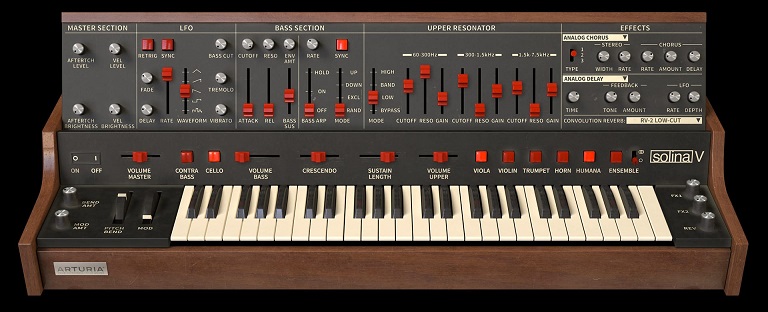

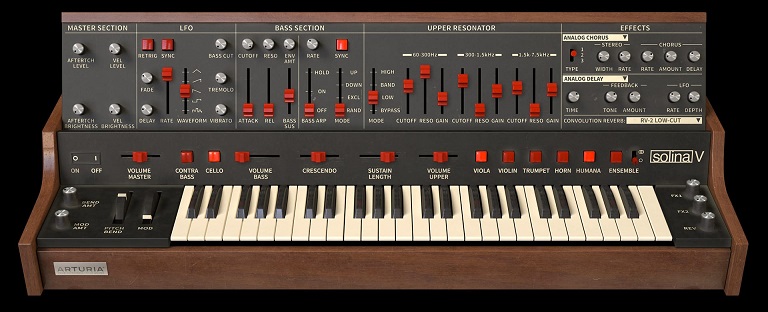

Arturia Solina-V

To be continued...

E-Mail Grant